Downeast Maine towns like Pembroke, populated by settlers of English

and Scottish background, converted forest oaks and pines into sailing

vessels. Intensely task-oriented and entrepreneurial, the Pembroke

residents built an iron foundry and, in their seaside yards, more than

150 vessels that sailed the oceans. The character of these people and the

success of their economy in the time of wooden ships ultimately produced

Ross Cottage, now a reminder of days gone by.

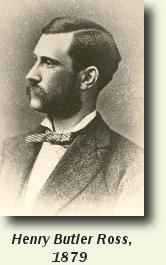

The story of Ross Cottage begins in tragedy, when Emelia (Willard) Ross,

the young wife of entrepreneur Henry Butler Ross (1845-1911), died in

childbirth in 1875 in Skowhegan. Heartbroken, yet in need of a mother

for his young daughter Mary Ella, Henry came to St. Stephen, N.B. on the

invitation of his brother Franklin to join him in the jewelry business

there. A mutual acquaintance apprised Henry of a feisty, independent-minded

young lady from Pembroke by the name of Lelia Bridges (1859-1943). They

married at the Bridges home in West Pembroke on May 1, 1879. Twenty years

later they acquired Ross Cottage.

Beyond her high spirits, Lelia Miranda Bridges represented two solid

families in a prosperous town. Her father, Henry Styles Bridges (1827-1904),

owned a general store. His great-grandfather Joseph, a Revolutionary soldier,

had settled in Pembroke in the 1780s. Henry served as a selectman and

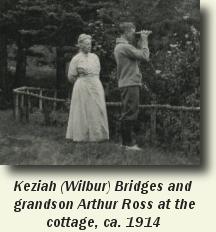

justice of the peace. Lelia’s mother, Keziah (Wilbur) Bridges (1829-1923),

was the daughter of Benjamin Wilbur, a farmer and itinerant Methodist

preacher who also served as a selectman. The Bridgeses and Wilburs

typified the people who raised Pembroke to its height in the 1870s.

Lelia’s social standing appealed to Henry, who aspired to prominence in

the St. Stephen-Calais border community. A descendant of Scottish immigrant

David Ross who arrived in Penobscot Bay in 1820, he wanted to make his mark

in business. His brother Franklin had moved in 1869 from Skowhegan to

St. Stephen where he established the jewelry store. When Henry joined

his brother they named the business Ross Bros. People freely crossed

the border in those days, and the brothers opened a branch of the store

in Calais in 1882. Henry and Lelia relocated to Calais from St. Stephen

in 1889 or 1890. After Henry’s death in 1911, Lelia bought out brother

Frank’s share of the Calais store.

Ross Bros. did well, thanks in part to Henry’s managerial skills and expertise

as an engraver. More importantly, the store – and the border cities – owed

their success to the white pines being stripped out of the woods, driven

down the St. Croix River to sawmills in Baring, Upper Mills, and the two

Milltowns, and loaded on schooners at Calais to be sailed down the coast

to build homes in cities along the Atlantic Seaboard. A goodly share of

the profit found its way into Ross Bros., the largest jewelry outlet east

of Bangor. That won Henry Butler Ross the wealth and status he sought

and enabled him to send his children to college. His obituary described

him as “an upright, honorable man in all the relations of life.”

Lelia bore Henry five children: Carl (1883-1950), Florence (1885-1964),

Jessie (1889-1980), Ruth (1893-1993), and Arthur (1898-1971). Arthur,

said the doctor who delivered him, appeared to be sickly. The doctor

advised, in the British tradition, that a seaside cottage would help

restore the boy’s vigor. Lelia’s family ties made Pembroke the logical

choice. A search located a southeast-facing cove on Hersey Neck along

East Bay that featured a wide red beach and a splendid spring. The land

belonged to the heirs of Frederick C. King, a farmer who had worked as a

cook on an oceangoing vessel. The farm took in most of the end of

Hersey Neck. Coincidentally, it included land that Joseph Bridges,

Lelia’s great-great-grandfather, had farmed in addition to his settlement

across the bay on Birch Point.

Lelia bore Henry five children: Carl (1883-1950), Florence (1885-1964),

Jessie (1889-1980), Ruth (1893-1993), and Arthur (1898-1971). Arthur,

said the doctor who delivered him, appeared to be sickly. The doctor

advised, in the British tradition, that a seaside cottage would help

restore the boy’s vigor. Lelia’s family ties made Pembroke the logical

choice. A search located a southeast-facing cove on Hersey Neck along

East Bay that featured a wide red beach and a splendid spring. The land

belonged to the heirs of Frederick C. King, a farmer who had worked as a

cook on an oceangoing vessel. The farm took in most of the end of

Hersey Neck. Coincidentally, it included land that Joseph Bridges,

Lelia’s great-great-grandfather, had farmed in addition to his settlement

across the bay on Birch Point.

Birch Point could be seen from the cottage. All the land across the bay

and, for that matter, all of what is now Perry, Pembroke, and Dennysville

once belonged to General Benjamin Lincoln. A Revolutionary War officer

from Hingham, Mass., he allocated 100-acre parcels to Joseph Bridges and

other veterans of his regiment on the condition that they settle and

improve the land. He hoped to build a population to sustain his lumber

business.

Henry bought the cottage property, a one-acre site, for $25. Ever the

frugal Scotsman despite his ample means, he preferred not to have his

cottage built from scratch. Instead he found a shoe shop going out of

business in St. Stephen and purchased the building. According to family

lore, in 1900 Henry had it loaded on a boat in two or three sections,

taken to Pembroke, landed on his beach, and hauled up onto a perch twenty

feet above the high tide line. Workmen added two second-story bedrooms

projecting over the porch facing the bay and, later, a kitchen and storage

shed on the lee side. .